Before the storm broke, Lili Márkus on holiday in Kanzelhöhe, Austria 1934

Before the storm broke, Lili Márkus on holiday in Kanzelhöhe, Austria 1934 With Max Sebald and issues of memory and loss currently never far from my mind, I have been rather fixated recently on a story embedded in a guide to an exhibition of

Hungarian Craft, Design and Architecture that took place at the University of Strathclyde's Collins Gallery in 2008 .(1)

An exhibition showing many of the same works is I understand about to take place at the

Museum of Applied Arts in Budapest (2).

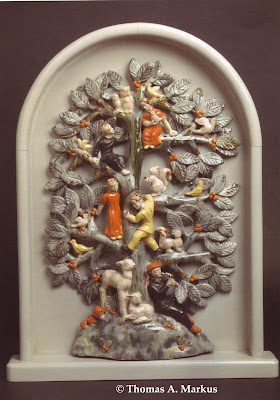

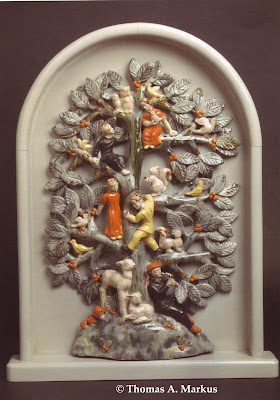

Tree Relief c. 1939 Victoria and Albert Museum

Tree Relief c. 1939 Victoria and Albert Museum Lili Márkus, around whose life and work the exhibition centred, came rather late to ceramics, but within a remarkably short space of time was exhibiting her work at exhibitions in Milan, Tallinn, Riga, Helsinki, Amsterdam, Oslo and Paris.

Lili's life falls neatly into three phases and three locations: Croatia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; Budapest and finally Greater Manchester.

Born in 1900 in Gyurgyenovác near Eszék, in what is now Croatia, to a family of German Jewish origin (Engels/Elek), Lili was exposed to a range of traditional crafts which were to influence her for the rest of her life. (3)

A peaceful childhood among the woods which her father managed was brought to a close by the shots fired at Sarajevo on June 28th 1914, which were to spell the end of the multi ethnic Austro-Hungarian Empire, and to unleash forces that would shatter the lives of millions of its inhabitants for generations to come.

In 1920, by the Treaty of Trianon, Hungary was stripped of three quarters of its pre-war territory, and Lily's family found themselves living in a new country composed of ethnic Romanians, Slovaks and South Slavs.

Lili Márkus 1923

Lili Márkus 1923 In January 1923 Lili married Győző Márkus and moved to Budapest, carrying with her anxiety about her parents and siblings left behind in what had become the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. (4)

In Budapest she moved into the upper middle class world of Hungary's assimilated Jewish community: her husband converted to Lutheranism in the 1920's, and she to Catholicism in the early 1930's. Through the contacts of her husband, an engineer in the family firm, Márkus Lajos, she entered a sophisticated world of architects, designers and manufacturers and was exposed to a modernist aesthetic. The change in her life from its beginnings in the woods of Croatia is symbolised by the remodelling of the family apartment in Budapest by the architect Kozma Lajos.

Living Room in the Márkus apartment

Living Room in the Márkus apartment  Library in the Márkus apartment

Library in the Márkus apartment Her own space revealed her love of colour and traditional designs.

View towards Conservatory (The Studio) in the Márkus apartment

View towards Conservatory (The Studio) in the Márkus apartment With the support of her husband, who had a kiln installed for her in the family firm, and in an environment in which women ceramicists were accepted and the decorative arts promoted by a Government keen to enhance the reputation of the new and much reduced Hungary, Lili's career flourished.

She completed her first formal training only in 1932, but exhibited in Milan the following year. An associate of

Margit Kovács, who was to become very famous in post-war Hungary, she looked to be on the verge of a very successful career in ceramics.

Chess Set exhibited at Paris in 1937, Cranbrook Academy of Art

Chess Set exhibited at Paris in 1937, Cranbrook Academy of Art It is I think impossible to improve on Juliet Kinchin's overall judgement on Lili's work at the height of her career,

"impressive both in range and quality" and a "confident assimilation of modern European styles, Hungarian folk culture and religious imagery into a sophisticated urban aesthetic" (5)

But all this came to a hurried end in the summer of 1939 when with her two sons, her sister in law and her fur coat she furtively left Hungary via Italy to join her husband and brother in law in the unlikely setting of Glossop in the Derbyshire hills.

A depressed town on the edge of Greater Manchester with high unemployment and a number of empty textile mills, Glossop was an ideal place to set up factories as Britain geared up for war, and the Markus brothers, who machined parts for Spitfire planes, were not alone in doing so. It was perhaps not so suitable for a Hungarian potter whose "colourful figurative tradition of ceramics" was at this time rather looked down on by the studio potters of England. Away from the intellectual and artistic circles in which she and her husband had moved in cosmopolitan Budapest, " how damp, depressed and provincial life in Glossop often must have seemed!" (6)

Her early years in England were overshadowed by the news leaking out of central Europe. Her elder brother went into hiding in Osijet, her younger brother disappeared, her mother was shot trying to escape and her father was sent to a death camp. (7)

Apart from a small exhibition at the Batsford Gallery in London in 1946, containing pieces of tapestry as well as ceramics, at which the V & A museum purchased the most expensive piece (The Tree Relief shown above), Lili never achieved anything remotely resembling the recognition and commercial success that she had achieved in such a short time in Hungary. She continued though to produce a range of pieces, some of which were sold through Heals' in London and Kendal Milne in Manchester,

Fireplace at "Ariel" , the home the family built in Glossop

Fireplace at "Ariel" , the home the family built in Glossop but much of her energy went on creating things for the new house, "Ariel", which they built on a windy hill overlooking Glossop, which must have contrasted with the view of the Danube that could be seen from their apartment in Hungary.

Finding increased comfort in her religious faith from 1953, she died after an illness at "Ariel" in 1962.

Postscript : "forgetting is what keeps us going.." - Max Sebald  Lili's eldest son, in the library in the Budapest apartment

Lili's eldest son, in the library in the Budapest apartment Born in October 1924, the eldest son, Robert, who was to become a distinguished medieval historian, must have been very aware of what was going on in his teen years in Hungary. Not surprisingly perhaps he blocked it out and, according to the writer of one of his

obituaries, concentrated on becoming an "unmistakable English gentleman." Returning to Hungary many years later he was moved to tears at the sight of the places he knew from his childhood.

My thanks to Professor Thomas A. Markus for kind permission to reproduce photos and quotations from

In the Eye of the Storm. The interpretation and the judgements made are of course entirely my own.

-----------------------------------------------

1. Juliet Kinchin,

In the Eye of the Storm: Lili Márkus and Stories of Hungarian Craft, Design and Architecture 1930-1960 University of Strathclyde 2008 ISBN: 978-0-947649-24-1.

2. At the time of writing details are not published on the museum's web site, but the exhibition will I understand run from March 1st to 30th April. It will feature the work of Márkus Lili, Márkus Lajos ( Lili's father in law and founder of the family firm) and the modernist architect Kozma Lajos.

3.

In the Eye of the Storm. p. 7

4. from 1929 it was renamed Yugoslavia.

In the Eye of the Storm. p. 13

5.

In the Eye of the Storm. p 5

6

In the Eye of the Storm. p. 51

7.

In the Eye of the Storm. p. 44